Wine labelling – Nutritional information

May 19th, 2023 | Responsible Drinking

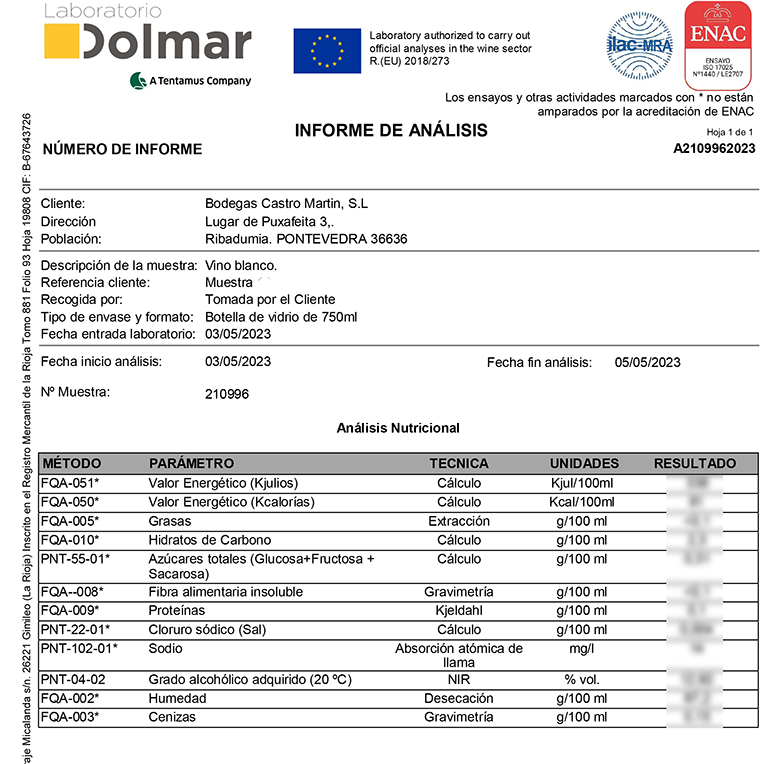

As from December 2023 we will be obliged to add nutritional information to our labels. Of course, with the amount of information already appearing on labels (including government health warnings etc.), there is a danger that the label might eventually cover most of the bottle! This leaves us with two options, either produce bigger bottles, or add a QR code to the label linking consumers directly to the information. (The first option of bigger bottles was very much tongue-in-cheek and we have used option two).

Suffice to say that in the very near future we will start to print labels with this new QR code included. (We do already include QR codes that links to the product page of the wine being consumed). The new QR will replace this, but this new link will still include information about the wine itself, so not all will be technical information.

In the meantime, we have already posted nutritional information on our website. On each product page (English and Spanish) there is a link under the downloads (descargas) section. The same link also appears under the general ‘downloads’ header on our homepage. All of these links are clearly marked ‘Nutritional Information’.

Of course, I should have pointed out from the offset, that there is no official recognition or certification for the category of ‘natural wine’ – but clearly, as the name implies, they are simply made in the most natural way possible, with nothing added and as little as possible taken away. As I have mentioned before, the downside can be that the wines themselves are inherently unstable. For example, a natural wine might have no sulphur added (leaving them prone to oxidation), they might not be fined to remove proteins (leading to protein instability and cloudiness in the wine). They are also largely unfiltered – a process that cleans the wine, but also removes body and flavour (according to the type and level of filtration used). In the case of natural white wines, they will certainly not be cold-stabilised (and can therefore develop tartrate crystals in the bottle). If the consumer is happy with this, and accepts a multitude of potential flaws, then why not?

Of course, I should have pointed out from the offset, that there is no official recognition or certification for the category of ‘natural wine’ – but clearly, as the name implies, they are simply made in the most natural way possible, with nothing added and as little as possible taken away. As I have mentioned before, the downside can be that the wines themselves are inherently unstable. For example, a natural wine might have no sulphur added (leaving them prone to oxidation), they might not be fined to remove proteins (leading to protein instability and cloudiness in the wine). They are also largely unfiltered – a process that cleans the wine, but also removes body and flavour (according to the type and level of filtration used). In the case of natural white wines, they will certainly not be cold-stabilised (and can therefore develop tartrate crystals in the bottle). If the consumer is happy with this, and accepts a multitude of potential flaws, then why not?